A recent Wall Street Journal article packed with scary imagery around methane emissions from the U.S. oil and natural gas industry relied on misleading data and biased sources to highlight an issue producers have well in hand. While the piece highlights some important, voluntary industry initiatives underway to further reduce emissions the result is an incomplete portrayal of emissions that the industry has demonstrably reduced despite rising production across the country.

Here are five key facts that provide needed context to the article:

Fact #1: Oil and natural gas systems are not the leading U.S. methane emissions sources.

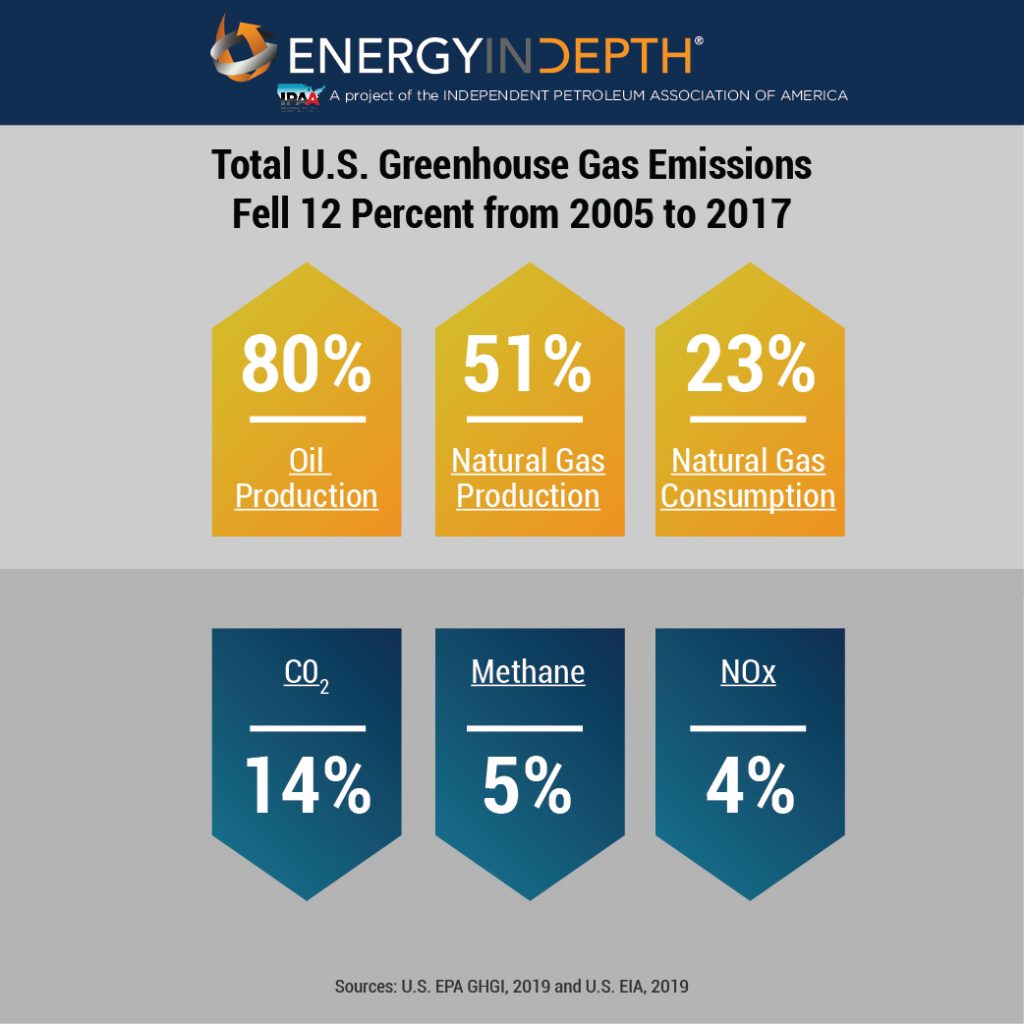

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency reported total U.S. methane emissions of 656.3 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent (Mmt CO2e) in 2017, according to its most recent Greenhouse Gas Inventory (GHGI).

The WSJ article includes a chart of various sources by percentage of total U.S. methane emissions. Not only did the author cite a higher total emissions figure, but in an article focused on oil and natural gas, it combined all energy sources into one category, which is misleading.

Realistically, oil (petroleum) and natural gas systems represented about 31 percent of total U.S. methane emissions in 2017, below the combined share of agricultural sources.

Fact #2: Methane emissions are declining in the top U.S. shale basins.

Methane emissions from U.S. oil and natural gas systems have declined 12 percent since 2005 and 14 percent since 1990, according to GHGI data, while production has skyrocketed.

Reducing methane emissions is a top priority in the oil and natural gas industry, and voluntary efforts are having significant results. For instance, 65 of the country’s leading energy companies recently reported that inspections of their operations determined only 0.16 percent of potential leak sources required repairs. That indicates a leakage rate much lower than previous EPA estimates. More importantly, participating companies fixed 99 percent of identified leaks within 60 days of detection.

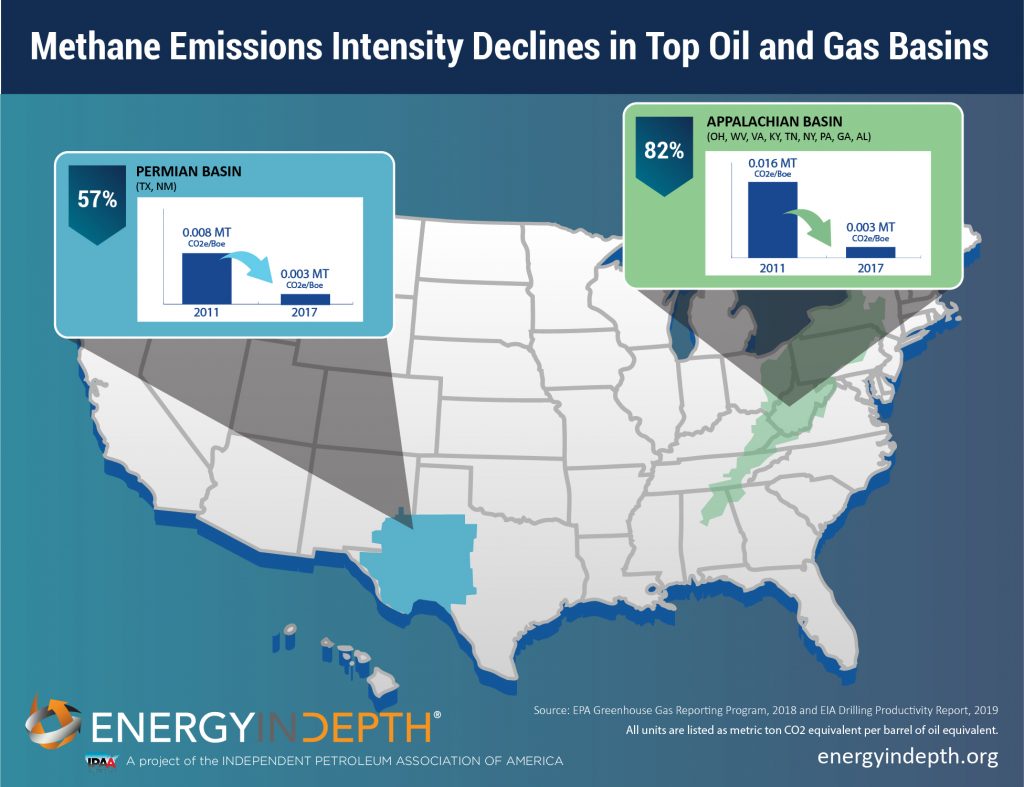

A recent EID analysis of EPA and U.S. Energy Information Administration data found that both methane emissions and intensity – emissions per unit of production – have declined in the top U.S. shale basins.

In the Permian Basin – the top producing oilfield in the world – annual methane emissions from production fell from 4.8 million metric tons (MMT) to 4.6 MMT from 2011 to 2017. Simultaneously, combined oil and natural gas production increased from 638.9 million barrels of oil equivalent (Boe) to 1.4 billion Boe. The result was a 57 percent reduction in methane emissions per unit of oil and gas produced.

Likewise, in the Appalachian Basin – the third highest natural gas producing region in the world – combined oil and natural gas production grew from 322 million Boe to 1.5 billion Boe from 2011 to 2017. At the same time, methane emissions from production in the basin fell from 5.3 MMT to 4.7 MMT, resulting in an emissions intensity reduction of 82 percent.

This context was absent from the WSJ article. Nor was there any mention of a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration study this year that found statistically insignificant trends for increased oil and natural gas methane emissions. Further, the NOAA study determined that after analyzing a decades-worth of data:

“Recent studies showing increases of methane emissions from oil and gas production have overestimated their volume by as much as 10 times.”

Instead, the reporter relied on a flawed 2018 study that estimated methane emissions in 2015 to be 60 percent higher than EPA estimates to bolster the argument that these leaks are happening at a greater rate and “threaten to derail the dominance of gas in the new energy world order.”

Fact #3: Methane leakage rates are far below the threshold for natural gas to maintain its climate benefits.

Even if the emissions study cited by WSJ is accurate in its claims that methane leakage rates are at 2.3 percent, these rates are far below the threshold for natural gas to achieve its climate benefits. In fact, the same organization that wrote that study also claims that natural gas maintains these benefits as long as rates stay below 3.2 percent.

Other studies have placed that bar far higher. A 2015 Carnegie Mellon University study found that over the entire lifecycle of liquefied natural gas – from production to consumption – as long as the methane leakage rate stays below roughly 9 percent when used for electricity and 5 percent for heating, LNG will maintain its climate benefits over traditional fuel sources.

Similarly, a 2019 study published in Nature determined:

“We found that the coal-to-gas shift is consistent with climate stabilization objectives for the next 50-100 years. Our finding is robust under a range of leakage rates and uncertainties in emissions data and metrics. It becomes conditional to the leakage rate in some locations only if we employ a set of metrics that essentially focus on short-term effects. Our case for the coal-to-gas shift is stronger than previously found…”

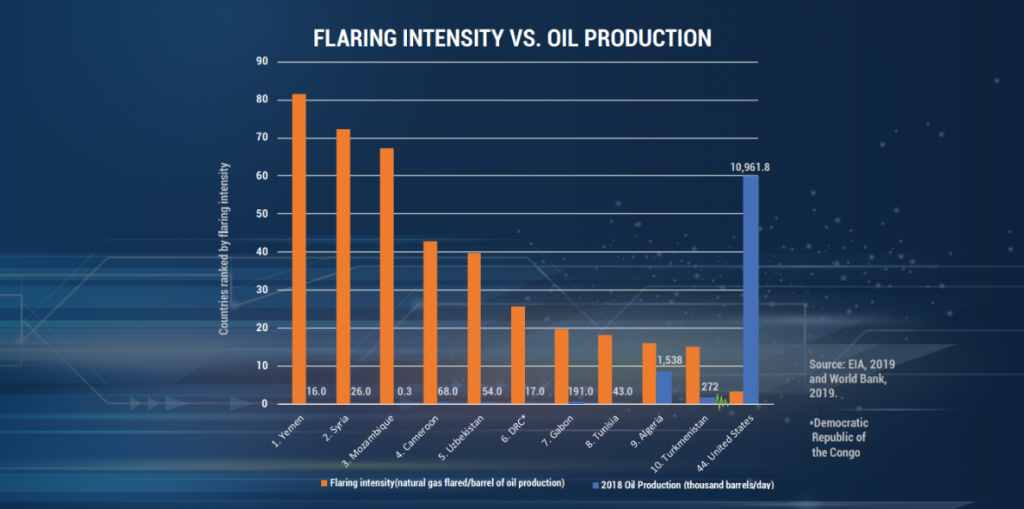

Fact #4: The United States has one of the world’s lowest flaring intensities despite having the highest oil and natural gas production.

One of the major focus areas in the article is on the industry’s use of flaring – a highly regulated practice used to safely alleviate issues that could arise from associated gas, or natural gas that is unintentionally extracted during oil production.

As the WSJ alludes, increased pipeline takeaway capacity will help to greatly reduce the need to flare in places like the Permian Basin. However, overall U.S. flaring is never given any perspective in the article.

The United States produces more oil and natural gas than anywhere else in the world. And yet it is never mentioned – despite the author referencing the organization’s data – that World Bank data show that the United States ranks 44th in the world for flaring intensity – flaring per unit of production.

Fact #5: FLIR cameras do not provide scientific evidence of methane leakage rates.

The WSJ dedicates an entire section of the article (and images throughout) to the “Keep It In the Ground” group Earthworks – an organization that vehemently opposes fracking and stood by its organizer, Sharon Wilson, when she equated it with “rape” – particularly its use of infrared cameras to “detect methane leaks.”

Aside from Wilson’s or Earthworks’ biased agenda never being mentioned, the article leaves out that even Earthworks has admitted its images from FLIR cameras offer no scientific evidence of methane leaks, explaining:

“No air quality tests were conducted in connection with the infrared drone photographs to quantify what amount of methane or other pollutants, if any, were being emitted at the named well sites.”

On the “measurements” taken by the cameras, Wilson has even said:

“We can’t say which VOCs or how much.”

Further, the majority of the hundreds of complaints mentioned in the article that Earthworks has made have been investigated and were determined to be false alarms.

Conclusion

Record oil and natural gas production has been a game-changer for the United States in recent years. Through technological innovation the industry continues to reduce its environmental footprint, and provide the world with affordable energy, while simultaneously helping it to significantly reduce emissions.

And while methane emissions will continue to be an important focus area for the industry, it’s clear that existing voluntary efforts are already having significant results. And those results provide critical context in any discussion of emissions.