The Environmental Defense Fund’s new calculations of methane leakage in the Permian Basin are still undergoing scientific review, but that didn’t stop the organization from releasing its figures – based on questionable methodologies and assumptions – alongside a map of alleged methane leaks in the basin.

Identifying and fixing methane leaks is a priority for U.S. oil and natural gas operators, and EDF’s work in this space could be very useful in helping industry to achieve greater success in doing so. However, this new report appears to have been more focused on grabbing headlines than finding solutions. In fact, unlike EDF’s past research, this analysis has yet to be peer-reviewed:

“We’re using proven scientific methods to measure methane, and intend to publish our results in peer-reviewed scientific journals. Because verifying the accuracy of the data is so crucial, and [sic] independent scientific advisory panel is reviewing our methods.”

Here are four important things to keep in mind when reading EDF’s new report and map:

#1 Questionable methodology to calculate Permian leakage rates

While disappointing, it’s not surprising that EDF’s estimated 3.5 percent methane leakage rate for oil and natural gas operations in the Permian is what’s getting headlines. After all, that figure is higher than most calculations for the national rate and it’s being claimed in the largest oil field in the world. But digging deeper into EDF’s methodology reveals this figure is likely exaggerated due to the exclusion of oil and natural gas liquids production data.

According to EDF:

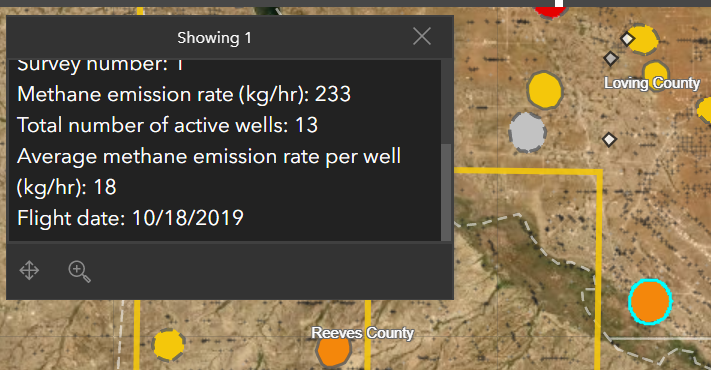

“We used ArcGIS to select and aggregate January daily average gas production within the flight path. We converted this gas production value of ~7,300,000 Mcf/day into a methane production value of 4,672,000 kg CH4/hr based on assumptions of 80% methane content and 19.2 kg CH4/ Mcf. Therefore, 162,000 kg CH4/hr is equivalent to about 3.5% of methane production.” (emphasis added)

EDF is counting emissions from both oil and natural gas wells, collected via aircraft and on-the-ground sampling, as evidenced by multiple images of oil pump jacks on the map. But then instead of dividing those total emissions by total oil and natural gas production, EDF only uses natural gas production, resulting in a higher percentage.

Even though this eliminates a significant portion of the total production — especially in an oil field like the Permian Basin where natural gas production only represented a little more than one-third of total daily production in 2018 — EDF has recommended this practice for calculating methane leakage rates . In April 2018, the organization said:

“Though there are different ways to calculate an upstream oil and gas intensity target, generally we recommend: Total methane emissions from oil and gas production / Total natural gas production.”

Using total natural gas production instead of total overall production inherently will result in a larger emissions rate. It’s then boosted even higher by eliminating another 20 percent of total natural gas production, ostensibly to account for natural gas liquids.

In other words, the selective use of production data yielded a higher methane emissions rate than what is actually occurring. And this makes any attempt to compare EDF’s rate to those calculated using whole production numbers a true apples-to-oranges comparison.

#2 Leakage rate based on assumptions

While EDF uses multiple methods of measurement to improve the accuracy of its calculations, it’s still making significant assumptions – similar to those EID has identified in the group’s previous research – to reach its conclusions. Namely, EDF uses single-day observations that have limited geographical coverage to estimate the emissions across one of the world’s largest oil and natural gas basins. This type of data collection does not account for temporal or spatial variability, which can result in exaggerated emissions estimates.

This is an issue because there are normal activities and episodic events that occur on well sites, typically during the day, that do not reflect the average emissions from the site. These include releases that do not occur 24 hours a day but are often calculated as if they do.

For instance, if a well site is undergoing routine maintenance at the time that aircraft sampling is occurring, the instruments will pick up larger than normal methane emissions. Assuming that this is a continuous emissions event for a site without further investigating to determine if the observed “leaks” were spikes from episodic events or actual leaks can inflate the average and in turn the emissions leakage rate.

A 2017 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration study addressed this issue, explaining:

“[E]pisodic sources can substantially impact midday methane emissions and aircraft may detect daily peak emissions rather than daily averages that are generally employed in emissions inventories.”

NOAA found that episodic releases can account for a third of midday emissions, noting:

“Thus, a valid comparison of aircraft estimates with annualized inventories needs to establish the representativeness of midday activity data for annualized emissions… Episodic releases, rather than atmospheric variability, may also explain substantial day-to-day variability.”

Similarly, the National Academy of Sciences recommends combining “top-down” (aircraft) with “bottom up” (facility-level) measurements, which can help to identify some of this daytime and episodic bias:

“Coordinated, contemporaneous top-down and bottom-up measurement campaigns, conducted in a variety of source regions for anthropogenic methane emissions, are crucial for identifying knowledge gaps and prioritizing emission inventory improvements. Careful evaluation of such data for use in national methane inventories is necessary to ensure representativeness of annual average assessments.”

#3 Lack of collaboration with industry adds to uncertainty of findings

EDF’s study could have been an opportunity for collaboration with industry. Instead, the group appears to have targeted operators and excluded them from the process altogether.

EDF has previously made an effort to work with industry: In 2012, EDF collaborated with more than 50 oil and gas companies and 40 different research institutions to analyze methane emissions across the oil and gas supply chain. In fact, EDF often touts its collaboration with industry, calling it “a pragmatic approach.”

In this study, however, there is no evidence of collaboration with any of the operators presented. In overviews of the study, EDF only lists three collaborators, Penn State University, Scientific Aviation and the University of Wyoming; each specializing in one collection method. The lack of industry collaborators gives limited access to data collected on sites.

Collaboration with operators would have provided clearer results. A large majority of the data presented was collected with aerial surveys, rather than ground surveys, and in those cases where EDF managed to do both, there was a huge discrepancy between the reported numbers. If EDF would have collaborated with operators in the areas surveyed, it would have been able to better verify the results.

This study is not the first time EDF has excluded industry. In 2018, EID wrote about EDF’s lack of collaboration with industry and how this practice goes against National Academy of Science recommendations.

Ultimately, EDF seems more interested in sharing the results of their findings with external observers rather than those who can actually respond effectively to the findings in a timely matter: oil and gas operators. In fact, in its overview of the study, EDF clearly states who it is hoping to target: “policymakers, the public and community groups.” Unlike operators, these groups are not be able to adequately respond to any ongoing methane leakage.

#4 EDF had knowledge of leaks for months and didn’t notify industry

Perhaps even more alarming than the high leakage rate EDF claims to have found is the fact that an environmental organization had knowledge of potential leaks for months and presumably didn’t share them with well site owners. EID found flight dates on the map as far back as October , yet the data were not released until April.

Leaks and releases can and do occur, but collaborative efforts by the oil and natural gas industry to identify and repair them are well-documented. EDF is in fact working alongside the Oil & Gas Climate Initiative on satellite monitoring to improve these efforts, and many participating companies had well sites included in this latest research. OGCI companies invested approximately $7 billion into research to reduce the industry’s carbon footprint, including methane emissions, in 2018.

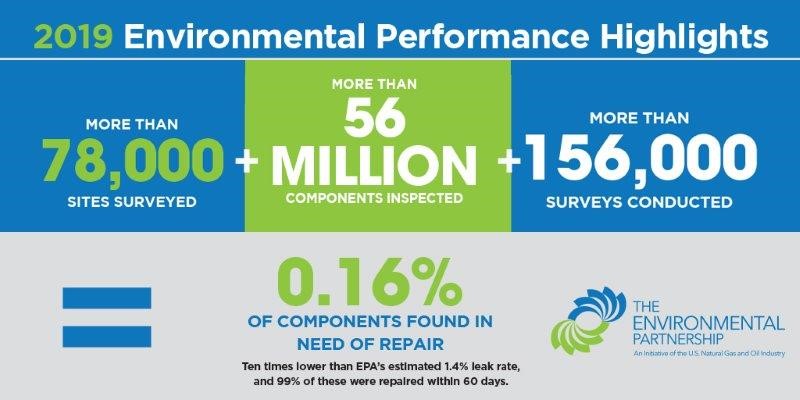

The Environmental Partnership, which also includes a large number of Permian producers, surveyed 78,000 well sites in 2019 and repaired 99 percent of identified leaks within 60 days.

At the end of March, trade associations and producers in Texas formed a consortium specifically focused on reducing methane emissions and flaring, including in the Permian Basin. The Texas Methane & Flaring Coalition is working to find “industry-led solutions to minimize flaring and methane emissions.” New Mexico similarly has a government-led Methane Advisory Panel that brings together industry and environmentalists – including EDF – to assist the state regulator in developing policies to reduce emissions.

Yet there’s no indication EDF used any of these existing channels to inform operators of potential leaks or to work with them to address them before making its headline-grabbing announcement.

Conclusion

Finding solutions to reduce emissions are important to everyone, and EDF has created something that could be incredibly helpful in that space by identifying potential issues. But the numbers generated by the work – and EDF’s months-long failure to inform and work with industry to fix these issues – deserve scrutiny and beg some questions about this group’s true intent.