A new University of Rochester study claiming methane emissions from fossil fuel activities are higher than previously estimated is encountering criticism from the scientific community because of significant limitations and the fact that it is at odds with existing research.

Contrary to headlines that gave the impression the study’s findings are written in stone, even the authors acknowledge their research – published in Nature – is far from complete and had significant limitations. As one author told the New York Times:

“Dr. Petrenko, one of the Rochester study’s authors, said that the huge undertaking of studying giant ice cores meant the study relied on a small sampling of data. ‘These measurements are incredibly difficult. So getting more data to help confirm our results would be very valuable,’ he said. ‘That means there’s quite a bit more research to be done.’” (emphasis added)

Here’s what methane scientists had to say immediately following the study’s release:

Research Does Not Support Finding That Fossil Fuel Emissions Are Higher

Methane scientist Daniel Jacob, a Harvard professor of atmospheric chemistry and chemical engineering, was quick to speak out on one of the biggest findings that media latched onto – the claim that fossil fuel methane emissions are higher than previously estimated. As Jacob told the Washington Post:

“’I totally disagree with this inference.’ If natural sources of fossil methane are smaller, he argued, that simply means total emissions are smaller — not that we should bump up emissions from another source in their place.” (emphasis added)

He further clarified his criticism to the NYT:

“Fossil fuel emissions are ‘based on fuel production rates, number of facilities, and direct measurements if available. The natural geological source is irrelevant for these estimates.’” (emphasis added)

Jacob has previously explained that oil and natural gas emissions are unlikely to be the cause of global methane spikes:

“The attribution that was pretty popular a few years ago was increasing natural gas. That’s gotten the wind knocked out of its sails a bit. We really don’t see evidence for that.”

And in the same article, this sentiment was echoed by others in the scientific community:

Research On Natural Fossil Methane At Odds With Existing Research

While Jacob believes there could be merit to the researchers’ finding that naturally occurring fossil methane is not as prevalent in the atmosphere as previously believed – a fact that he believes could mean total emissions are also lower than previously estimated – the Environmental Defense Fund was quick to point out that this may not be supported by existing evidence. EDF researcher Stefan Schwietzke told WaPo:

“The major question is now how to reconcile [the new study] with recent regional measurements.”

Schwietzke also listed a few examples of why the new findings don’t jibe with other emissions studies that have identified nearly as many emissions from singular locations as what the Univ. of Rochester researchers claim to be the total for all naturally occurring sources. From WaPo:

“He cited a recent study finding emissions of 3 million tons per year just from one sector of the Arctic ocean. Meanwhile, the Caspian Sea region is known for an abundance of huge mud volcanoes that belch methane, and the estimates for their emissions alone are ‘in the order of magnitude’ of total geologic emissions found by the new study, Schwietzke said.”

U.S. Oil & Natural Gas Methane Emissions Declining

The oil and natural gas industry is taking significant strides to reduce methane emissions in its operations. Not only are some of the world’s biggest oil and natural gas producers committing to reduce or stop flaring and voluntarily increasing methane leak detection monitoring – and then quickly fixing any leaks – but recent data shows these efforts are already paying off in the United States.

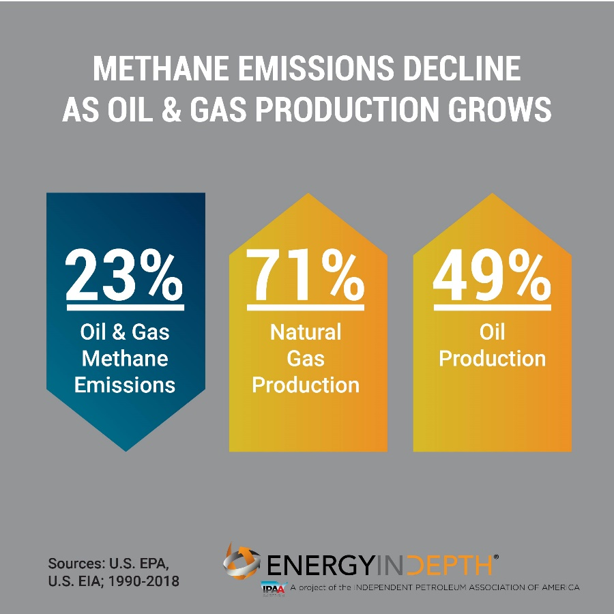

Draft Environmental Protection Agency data show that U.S. methane emissions continue to decline despite significant increases in oil and natural gas development. Not only did total U.S. methane emissions fall 1.2 percent from 2017 to 2018 – continuing a trend that has seen these emissions reduced by 13 percent since 2005 and 30 percent since 1990 – but petroleum and natural gas systems methane emissions have fallen 23 percent since 1990, at the same time that oil and natural gas production increased by 49 percent and 71 percent, respectively.

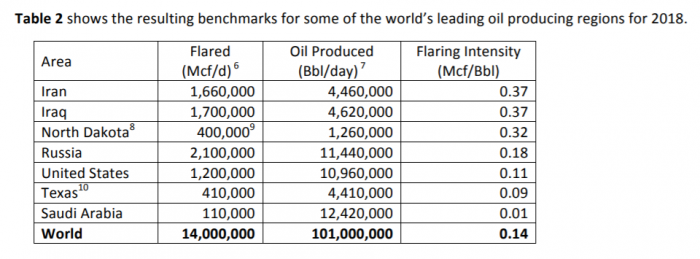

And a new Railroad Commission of Texas report found that flaring intensity in the United States is far below that of other major oil producing nations, despite U.S. oil and natural gas production outpacing that of other countries. RRC data show U.S. flaring was 0.11 in 2017, while the world average was 0.14 – far below Russia (0.18) and Iran and Iraq (each at 0.37).

Conclusion

To echo Daniel Jacob, while this latest research is an important addition to the ongoing discussion on global methane emissions and should be further evaluated, whether or not the study is accurate in its assessment of fossil fuel methane emissions is somewhat “irrelevant.” The bottom line is that the U.S. oil and natural gas industry is committed to reducing these emissions, and already making significant progress in doing so.