Here they go again. The people who concocted, financed and executed the “Exxon Knew” charade appear to have launched a new attack in their crusade to “establish in public’s mind that Exxon is a corrupt institution.”

Citizen Lab, a Canadian organization focused on cybersecurity, released a report yesterday on a hacking-for-hire group they call “Dark Basin,” which sent phishing emails to thousands of companies across multiple industries, government officials, activists, journalists, and others across six continents.

While these alleged attacks numbered in the thousands and targeted individuals, corporations, and government officials across the world, Citizen Lab and its “Exxon Knew” contributors (more on this below) sought fit to name and devote most of the focus of their report to a single company: ExxonMobil.

Why? Certainly not because of any evidence. But because…if they were the targets of phishing attempts, ExxonMobil must have been responsible! Of the dozens of outlets that covered this report, only the New York Times took the bait and made ExxonMobil the focus of their story, despite no evidence that the company was involved in any way. Reuters, which secured an exclusive and broke the story, didn’t even mention the company in their reporting.

Along with the hundreds of other institutions targeted, several environmental organizations closely tied to the “Exxon Knew” movement were subjected to the attacks, including the Rockefeller Family Fund, Climate Investigations Center, Greenpeace, Center for International Environmental Law, Public Citizen, and 350.org, among others. Citizen Lab reports that other groups were targeted but asked not to be named, though the report linked to several articles detailing leaked memos from organizations created by and affiliated with environmentalist billionaire Tom Steyer, who backs the “Exxon Knew” campaign.

Outrageously, the only reason ExxonMobil is even mentioned in a report about the Dark Basin hacking group is that they themselves are the continued focus of a coordinated attack by the aforementioned environmental groups. Indeed, the groups listed above all participated in a secret meeting to hatch a strategy to “establish in public’s mind that Exxon is a corrupt institution.” Ironically, by coming forward in this report the “Exxon Knew” groups are admitting they are part of a conspiracy to attack the company.

It should also be noted that hackers are savvy social manipulators. In any phishing attempt, they focus on material they know their target would care about. For any outsider, it would be easy to identify ExxonMobil as a subject they care very, very much about – some of these organizations have even dedicated entire webpages to their campaign against ExxonMobil – and send them malicious links referencing the company, which is what happened.

The report links Dark Basin with “high confidence” to an Indian company, BellTroX InfoTech Services. The report mentions zero ties between BellTroX and ExxonMobil or ExxonMobil employees. In fact, the only vague point that could associate ExxonMobil with BellTroX is that BellTroX claims to work with big corporations, and ExxonMobil is indeed a big corporation.

At one point in the investigation, Citizen Lab realized that NortonLifeLock was pursuing a parallel investigation into BellTroX. They shared intelligence, and NortonLifeLock published their findings on the same day as Citizen Lab, which incidentally revealed the extent to which Citizen Lab distorted their findings to focus on the “Exxon Knew” campaigners.

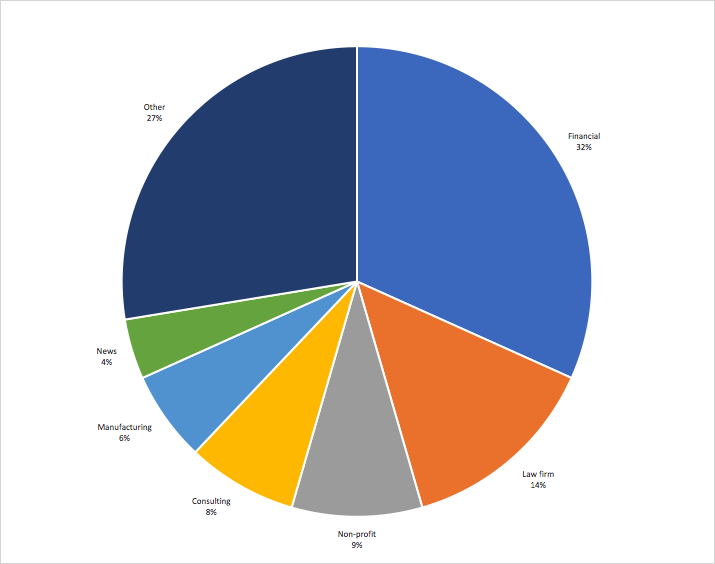

NortonLifeLock reports that 32% of the hackers’ targets were related to financial services, 14% were law firms, and 27% were “Other.” Non-profits, including those that were the focus of the Citizen Lab report, represented only 9% of the targeted groups.

Image Credit: NortonLifeLock; “Mercenary.Amanda: Professional Hackers for Hire carried out large-scale credential spearphishing campaigns since at least 2013”

The Citizen Lab report also almost entirely skipped over the fact that it wasn’t just environmental groups that Dark Basin pursued, but others in the energy industry. In a very brief paragraph, Citizen Lab wrote:

“Targets ranged from lawyers and staff to CEOs and executives. In some cases, we observed large swaths of the energy and extractive industry targeted in a particular country, ranging from oilfield services companies and energy companies to prominent industry figures and officials at relevant government offices.”

The New York Times similarly downplayed the extent to which entities and individuals other than those active in the “Exxon Knew” campaign were the target of this operation, though it did note that ExxonMobil has not been accused of any wrongdoing. Most other outlets covering this story didn’t even mention the company, likely because there is zero evidence that ExxonMobil was involved in or affiliated with this hacking ring.

A reasonable person would infer that there are many foreign actors or other malicious entities that would pay big bucks for their services. So why are environmental groups, Citizen Lab, and the New York Times suggesting that ExxonMobil may be involved?

A Closer Look at Citizen Lab

One answer may be that Citizen Lab is funded by many of the same groups funding the “Exxon Knew” campaign, including the Hewlett Foundation, Oak Foundation, and Open Society Foundation. Furthermore, Citizen Lab specifically acknowledges the help of Kert Davies and Lee Wasserman – both figures that have played central roles in spurring and promoting climate litigation against ExxonMobil and other oil and gas companies.

Within the Dark Basin report itself, they also thank a fund named Mountain Philanthropies for financially supporting their research.

Because Mountain Philanthropies is a limited liability company, it is not required to disclose either its funders or grantees. However, Mountain Philanthropies is a project of Arabella Advisers, a left-wing dark money consulting group. Not only is Arabella Advisors’ address listed under Mountain Philanthropies’ contact information on the homepage of their website, but the group’s CEO Michael Madnick was previously the treasurer of one of the four main funds that Arabella controls, the Sixteen Thirty Fund. In fact, Influence Watch, a project of the Capital Research Center, lists Mountain Philanthropies as a “child organization” of Arabella Advisors.

Arabella Advisors has been the subject of several investigations on “dark money” within progressive causes, including climate change. One of those investigations found that between 2013 and 2017, the four funds managed by Arabella received $1.6 billion in contributions to advance its donors’ agendas through dozens of “pop-up” groups and “astroturf ” initiatives.

Many of the leading funders of the “Exxon Knew” campaign, including the Rockefeller Brothers Fund and Rockefeller Family Fund, are donors to the funds managed by Arabella.

The Citizen Lab report is also notable for what it gets objectively wrong. In what appears to be an attempt to suggest that the hacking was related to major developments in the “Exxon Knew” campaign, Citizen Lab produced a timeline plotting upticks in hacker activity to key milestones in the legal campaign against ExxonMobil. But the organization misses a lot of key details and gets other facts just plain wrong in what appears to be an attempt to fit the activists’ narrative.

The timeline begins with the previously mentioned secret meeting where the activists plotted their campaign against ExxonMobil. Citizen Lab and the meeting participants suggest that the meeting agenda may have been “stolen” as a result of the phishing attempts, ignoring the possibility that the email was leaked. They provide no evidence to back up their claim that the agenda may have been stolen.

Citizen Lab then suggests that a filing from the New York attorney general in their case against ExxonMobil on June 2, 2017 prompted a flurry of activity (New York lost their case last year and declined to appeal, prompting handwringing from activists). But that filing was but one of many in the lengthy investigation that stretched on for years and was not likely to have spurred specific activity.

What is far more likely is that these environmental groups were engaging in their own flurry of activity at the time to respond to President Trump’s announcement on June 1, 2017 that he would be withdrawing the United States from the Paris climate accord. Nearly every group listed in the Citizen Lab report issued statements and published blogs and op-eds criticizing the president’s move, which may have prompted scrutiny of the groups from the hackers.

Citizen Lab also says the New York attorney general filed their lawsuit on January 8, 2018, which is off by 10 months. The milestone is an arbitrary marker anyway, as the hacker activity ceased a month prior.

Let’s be abundantly clear – hacking is an awful, illegal practice. As frequent targets of phishing and other hacking attacks ourselves, we don’t wish it on anyone. Hacking individuals or organizations is not only violating, but a fundamental threat to democracy.

However, it’s appalling to watch the environmental activists, who have accused ExxonMobil of misdeeds in the past, be so quick to throw this global hacking ring on the company, despite zero evidence that they are behind or in any way associated with the attack or the group perpetrating it.

In one tweet, 350.org co-founder Jamie Henn wrote: “I got dozens of these emails, along with so many of my colleagues. Considering how hard Exxon’s lawyers and the GOP tried to get our emails, hard to believe there’s no connection. #ExxonKnew.”

Lee Wasserman, executive director of the Rockefeller Family Fund – which is bankrolling the entire “Exxon Knew” campaign – told the Financial Times: “I’m not saying that they were directly responsible for this but someone was concerned about our efforts, it’s pretty safe to say.” Wasserman’s quote was removed after a few hours, though FT did not disclose the update.

This report from Citizen Lab raises more questions than it answers. Why did Citizen Lab and the New York Times focus so intently on the activists involved in the “Exxon Knew” campaign when it was such a small portion of the overall operation? How many other environmental groups active in the campaign were attacked but didn’t want to come forward? What were the hackers hoping to learn from these groups, and to what end?